In Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan, there is already plenty to see in the city center, but there are also some fascinating places an hour or less away by road. Unfortunately, while public transport within the urban area is cheap and has decent coverage, it is practically nonexistent in outlying areas. The only viable option is to hire a tour guide with a car. We booked this online, although even for travellers lacking the foresight to book in advance, similar itineraries can easily be found from the many salespeople around Baku’s Old City.

At 9:30 in the morning, we were picked up from our hotel in a green Toyota Prius and set off for Gobustan, 50 km southwest of the city center. This area is best known as the location of the World Heritage Site Gobustan Rock Art Cultural Landscape. First, we stopped at the newly built museum there and our tour guide explained all of the exhibits. The museum is small, so this did not take too long.

Then, we had to go further up the road to the actual entrance.

The landscape of this area can only be described as otherworldly, as it is not obvious how such rock formations came to exist. Glacial activity from the last ice age seems to be the most likely cause, because few other things in nature have the power to move huge boulders on a large scale.

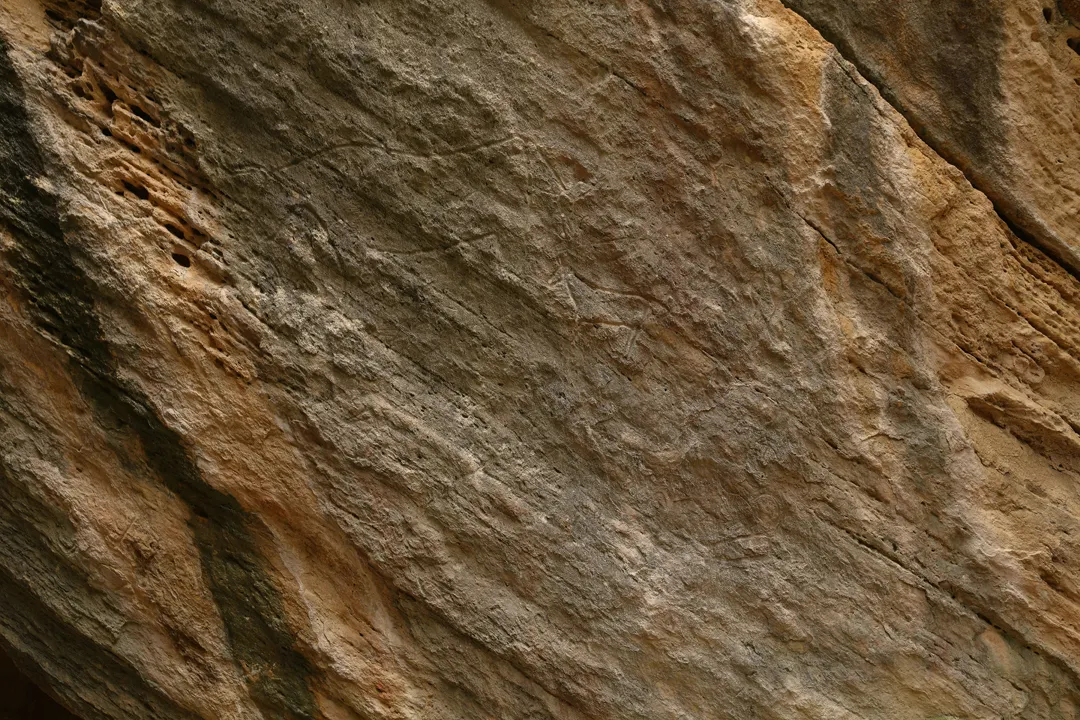

In any case, the geography here must have already reached its current state at least 20,000 years ago, when prehistoric humans began to create petroglyphs on Gobustan’s rocks. Such petroglyphs are among the world’s the oldest remaining artworks — no other way to record information even existed until the first written language was invented 5,400 years ago.

Having a tour guide for the rock art is almost necessary, particularly because most of the petroglyphs have become faded after millennia of exposure to the elements, so it is difficult to identify them (or in some cases, even to see them) without specialized knowledge. Without our guide’s explanations, we would have struggled to find or understand anything here.

While the petroglyphs are now located on a hillside several kilometers from the Caspian Sea, the water level was higher in prehistoric times, so this had once been a coastal area more suitable for habitation.

We finished our walk around the rock art area at the most recognizable geological feature, a natural overhang. From this perspective, it is easy to imagine the existence of a coastline here.

Then, we went back to the main road by car towards our next stop, the mud volcanoes. Half of all known mud volcanoes are found in Azerbaijan, specifically near the Caspian Sea at the eastern edge of the country. Gobustan has a large concentration, with 43 in total.

At the edge of the town, the paved road ends, and we had to switch to an antiquated Russian 4×4 car driven by a local resident for an additional cost of 40 manat.

For the rest of the way, the road consists entirely of mud. Or rather, everything consists entirely of mud; the terrain is brown and featureless as far as the eye can see. Such conditions could hardly have been a challenge to the driver, who had been doing this for at least 20 years. On the other hand, his vehicle had seemingly been designed with comfort as an afterthought, resulting in a cramped and bumpy ride.

We arrived at a place near a cluster of mud volcanoes, where there were already a few other tourists. Many photos of Gobustan online show the ground made of dried mud, but considering that it was February and everything was thawing after winter, there was not a single piece of dry ground anywhere. Mud in Eastern Europe is no simple obstacle, having ensnared Napoleon’s army in 1812 and Hitler’s in 1941. In order to step outside the car, we needed to wrap our shoes in plastic bags.

Fortunately, we only had to walk a few meters to reach a mud volcano. Those that can be safely visited are not much taller than an average person, although in Azerbaijan, there exist larger ones up to 150 m in height. They are formed by gases rising from beneath the Earth’s surface, and the mud constantly bubbles at the top where it flows out.

We tried to climb a few, but it was arduous because of how unstable the sides are. It was a good thing that neither of us fell, which would have been extremely unpleasant.

Aside from looking at the mud volcanoes closely, there is nothing else to do, so we were done there in less than half an hour. On the way back to Baku, we stopped briefly at the Bibiheybat Mosque, built on a hillside facing the Caspian Sea. However, it is a replica, the original one having been demolished by the Soviet government in 1934. Locals use it as a functional mosque, but few people were there in the middle of a weekday.

Since we were returning from somewhere south of Baku and heading towards the north, we ate lunch inside the city. It was actually the first chance for us to properly eat Azerbaijani food, because we had only eaten a cheap meal after arriving the previous evening.

After lunch, we got back on the road on a course that weaved through the densely populated northern suburbs of Baku. In an unassuming place on the fringes of the urban area is the Yanardağ, which translates to “burning mountain”. Here, natural gas leaks continuously from the ground; at some point, it was ignited and then started to burn uninterrupted due to the constant supply of fuel. This phenomenon is said to be one of the reasons that Azerbaijan gained the moniker “The Land of Fire”.

There were only a few other tourists, so we could easily approach the flames, but going any closer than the edge of the paved area is not allowed for obvious reasons. Interestingly, the fire stays at a relatively constant size and does not spread, because other than the natural gas, there are no flammable materials such as plants nearby.

Finally, we proceeded to the last place in the tour itinerary: the Atashgah, a temple for fire worship located at the western edge of Baku, a few kilometers southwest of the airport. It was originally built by Zoroastrians in the 17th century, but its relevance faded as Zoroastrianism declined and Islam became the dominant religion in the region. Today, it is maintained as a museum. Incidentally, there is a train station just outside the entrance, so it is the only one of the four places in the tour that would be feasible to visit independently.

The building has a pentagonal floor plan, shaped approximately like the outline of a house, or in other words, a rectangle topped by a triangle. Its structure is like that of a fortress, with outer walls surrounding a central courtyard. In the middle of the courtyard is a pavilion where an eternal flame burns.

At the time of the temple’s construction, the gas flowed naturally like at Yanardağ, but the source was depleted by the energy industry in 1969, so now the gas is drawn from utility infrastructure no differently than in normal buildings.

The outer walls contain irregularly shaped rooms, all of which face the courtyard. Some are closed while others contain museum exhibits.

It is not possible to go upstairs on top of the wall because the stairs are blocked, so after going inside each of the open rooms, we had seen everything at the Atashgah, and it was time to go back to our hotel.

From departure to return, the tour took around eight hours. Not only were there a decent variety of sights, but the travel time was reasonable, so overall, we considered it a good inclusion in our itinerary for 3.5 days in Baku.