It is universally known that Beijing is the capital of China. In Chinese, the literal meaning of the two characters in Beijing’s name is “northern capital”. Without knowing the language, it may not be obvious that there is also a “southern capital”: Nanjing, the 13th largest city in China with a population of 9.5 million. Today, it is merely the capital of the province of Jiangsu, but it has been the national capital at various times throughout history, as recently as 1949.

We reached Nanjing from Shanghai using a regional train in around two hours. Nanjing is also an intermediate stop for faster trains on the flagship Beijing-Shanghai route, but that line’s stations are outside the city centers, so the overall time savings would have been minimal.

As we arrived late in the afternoon, we decided to leave the sightseeing for the next day, and in the morning, we headed for Zhongshan Mountain National Park, which encompasses numerous renowned cultural and historical sites. It is located a short distance east of the city center and is easily reachable by metro.

The area closest to the entrance is used as a large city park and does not have anything particularly remarkable. If arriving by bus or car, this part can be bypassed, although it was a clear summer weekend, resulting in so much traffic that we were able to walk to the parking area faster than people who tried to go by road.

Additionally, there were a wide variety of flowers in full bloom along the path, so walking from the metro station proved to be a good choice.

Next to the parking area, some restaurants and convenience stores can be found. It was only 10:30 when we reached there, but we opted to have lunch early to avoid the inevitable crowds later. We ate noodles with roast duck (duck-based dishes are representative of Nanjing’s cuisine).

The main sights in Zhongshan Mountain National Park can be divided into three groups: east, west, and central. In the latter is Nanjing’s most famous landmark, the Mausoleum of Sun Yat-sen. Sun Yat-sen (1866-1925) was a revolutionary and national hero who had a monumental impact on Chinese history, being responsible for ending the monarchy and thus setting the stage for the rise of modern China. It was in Nanjing on January 1, 1912 that he declared the establishment of the Republic of China, having been elected as its first president. The construction of his final resting place began in 1926, several months after his death, and finished in 1933.

While the shapes of the mausoleum’s buildings are traditional, the materials are not; granite is used for the main structural portions and blue glazed tiles for the roofs, creating a unique and distinctive appearance.

The main gate bears an inscription of Sun Yat-sen’s most famous quote, “The world belongs to the people.” — a stark contrast to the monarchy, under which everything had been considered the property of the emperor.

Uphill from the main gate is a smaller building containing a memorial obelisk, and after that, the final and largest building, which houses Sun Yat-sen’s tomb.

After going back down, we continued towards the eastern part of the park, known as the Linggu Temple area. The temple has existed in some form since the 6th century, but during the 1920s and 1930s, a large portion of the temple grounds was converted into a war memorial. Currently, a functional temple can still be found here alongside the memorial.

Traces of the old temple can easily be seen in the war memorial’s architecture and layout.

It is a space for quiet reflection without large crowds. In fact, among the three parts of the park, it appeared to us to be by far the least popular.

The centerpiece of the war memorial is the pagoda, a 66 meter, nine-level structure built in 1931 using granite from Suzhou and reinforced concrete.

We climbed the 252 steps to the top, from where there are unobstructed views in all directions. There was negligible air pollution and therefore nearly unlimited visibility. It can be observed from the pagoda that the park is surrounded by highly built-up areas (and actually even completely within the bounds of the rectangle formed by the metro lines 2, 3, and 4). However, the park’s large size and dense forest cover make the city feel surprisingly distant from inside.

The skyline can be seen to the west; for this particular view, the light would be better in the morning with the sun in the east, so we ought to have directly come here first.

It could also be nice to see the night view, but that would only be feasible in the winter. As a matter of fact, when we descended from the pagoda with the sun still high in the sky, there was only one hour left until the park’s closing time, so we had to start walking back despite having only seen two-thirds of the main sights. We took a slightly different route, passing through the temple.

At the temple exit, we managed to find a bus back to the metro station. It was overcrowded, but fortunately, there was less traffic leaving than there had been entering earlier.

We needed to adjust our plans and return on the following day in order to visit the western part of the park: the Ming Xiaoling Mausoleum, the tomb of Zhu Yuanzhang, first emperor of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), who used Nanjing as his capital. The complex required 32 years to construct beginning in 1381.

The approach to the mausoleum is lined by statues of both real and mythical animals, the largest among them being the camels and elephants at over three meters tall. There are twelve pairs of statues for 24 total.

In terms of area, the Ming Xiaoling Mausoleum is much larger than the Mausoleum of Sun Yat-sen, though its architecture is more orthodox. When first completed, it was even larger than in its current form, some of the buildings having been lost over the centuries. The main gate itself was destroyed during the Taiping Rebellion in 1853 and was not restored until nine years later.

Nonetheless, the mausoleum remains the finest example of imperial architecture in the city, and it integrates harmoniously with its forested setting.

Crowds are unavoidable, but they tend to only go along the main axis, so it is easy to find spots without people by going off to the side.

The main building of the mausoleum is sixteen meters tall including the stone base. In the upper part of the structure, there are some exhibits detailing Zhu Yuanzhang’s remarkable rise from an impoverished background to become the emperor of China.

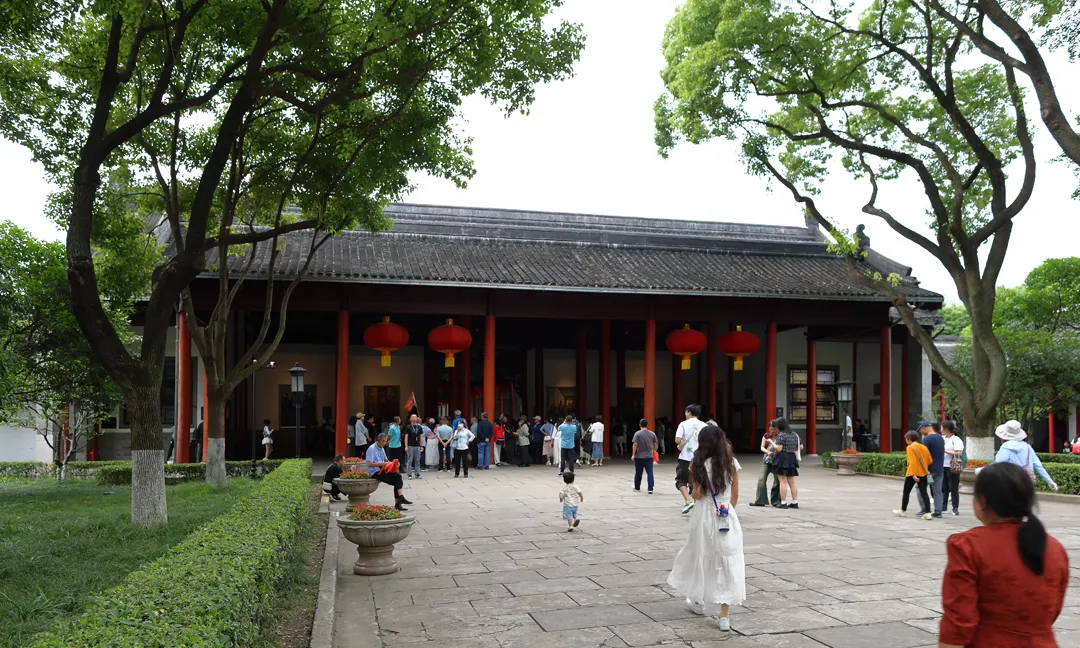

There are more things to see in the national park, but we had no time for them after already spending the better part of two days there. We left via the southwest corner and took a short metro ride to the old Presidential Palace. This complex was the seat of government when Nanjing was the capital of the Republic of China in 1927-37 and 1946-49 (in the intervening years, Nanjing was under Japanese occupation, and Chongqing temporarily served as the capital), and is one of the best surviving examples of Republican-era architecture.

In 1949, Beijing became the capital again when the People’s Republic of China was founded, after which the Presidential Palace was used as a local government office until the 1980s. Since 1998, it has been a museum. Contrary to the typically monotonous image of government buildings, large portions of the facility consist of classical gardens.

The western or Xu garden, which is the largest of the gardens, contains the iconic stone ship. It appears to float on the water’s surface but in fact has a solid limestone foundation on the bottom of the pond.

From some viewpoints, the traditional architecture can be seen juxtaposed with the ultra-modern city outside, which is always a fascinating contrast.

Most people go only to the front and central areas of the complex, but it is actually quite large. It was also near the closing time, which meant we could find uncrowded places as we went deeper inside.

Differences in architectural styles can be seen among the various buildings, since unprecedented political and social changes were occurring in China during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Buildings from the Republican era tend to have European influences and commonly have grey brick exteriors, while more traditional structures, some of which predate the 1911 Revolution, use wood and are painted white.

We looked around the various buildings and gardens in the eastern side and exited through the rear (north) just before the Presidential Palace closed.

Outside the Presidential Palace, along its northern and western walls, there are a lot of restaurants in Republican-style buildings, which are a mixture of a few actual historical buildings and mostly new construction from the 2000s. This area is known as Nanjing 1912 after the year that the Republic of China was founded.

We ate dinner at the “Nanjing Impressions” restaurant, which was recommended, but we had to wait nearly an hour for a seat, the food was not much more than average, and the service was questionable because the place was so full. It would have been better to find a normal restaurant somewhere else.

It turned out that three days was not enough to see everything in Nanjing, especially in the summer when the heat can be excessive during the daytime. We started our last day at the Zhonghuamen (Chinese Gate), the largest remaining city gate in China. Built during the Ming Dynasty, it is 118 m wide and 21 m tall.

The city walls of Nanjing are the best-preserved among all major Chinese cities and the longest (25 km) that can be seen anywhere in the world. The scale of the fortifications is such that although the current population of the city is around twenty times greater than in the time of the Ming Dynasty, the city center still appears distant when seen from atop the Zhonghuamen.

Surprisingly, few people were there considering its historical value and also how crowded the other attractions had been. We hardly encountered any other visitors at all.

While it is possible to walk along the top of the wall to reach the other gates, there is no shade and the wall is far too long to make this a reasonable option. We left after having an early lunch nearby and proceeded to Yihe Road, a neighborhood slightly west of the city center that is notable for having China’s largest concentration of Republican-era buildings, more than 200 of which are protected.

Unlike the wholly commercialized Nanjing 1912, Yihe Road is largely residential except for the one or two blocks at the entrance. It was the preferred place to live for government officials, the upper class, and foreign diplomats when Nanjing was the capital of the Republic of China. Numerous embassies were located here including those of the Soviet Union, Italy, Canada, Brazil, the Philippines, and India.

There were again few visitors, albeit somewhat more than at the Zhonghuamen. It was not really clear why; the area is picturesque, easy to reach using the metro, and well-maintained. One potential drawback is that the vast majority of buildings are still private houses and cannot be entered.

The part of Yihe Road where we saw the most tourists was a street lined with yellow walls and old trees. A residential area with such a historical atmosphere is extremely rare in China because rapid economic growth only began to occur in the 1980s, so very little high-quality housing existed before that time. For those of us who have grown up in modern cities, this is quite fascinating to see.

It was already late afternoon by the time we were able to get back to the main road, and we only had time to go to one more place: the Confucius Temple scenic area, a sort of old town, or more accurately, a tourist attraction designed to look like one. We found it more crowded than anywhere else in Nanjing, which seemed a bit odd since large Chinese cities more or less all have something similar to this.

Walking around these places can be interesting but it is hardly an authentic experience. The best things to do are limited to eating snacks and shopping for souvenirs.

It could be better if there were not so many people, but that could never be possible even on weekdays,

We stayed until after sunset so that we could see the illuminations, but then we had to go back to our hotel to pack and prepare for our departure the next day. In retrospect, one or two more days in the itinerary would have been helpful, but it is easy enough to reach Nanjing, so the option can still be left on the table for future trips.